Relation between Farming, Research, Extension, Gender & ICTs (Photo Credit: Ben Addom)

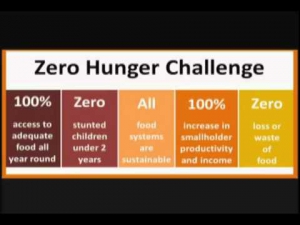

The main obstacle to food security (the availability, access, and utilization of food) in most agricultural-based developing economies is lack of human, technical and institutional capacity to produce and distribute the food. In this post, I bring together two arguments as the basis for addressing the challenge of capacity building in agriculture through the emerging value chain approach, and the role Information Communications Technologies (ICTs) can play to increase food security in some of these economies. Below are the arguments:

1) In the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) Gender and Rural Employment Policy Brief, No. 4 (2010) issue, the editors asked an important question – whether the agricultural value chain development could be a threat or opportunity for women’s employment? The authors argued that the value chain development can provide opportunities for quality employment for men and women but at the same time perpetuate gender stereotypes that could keep women in lower paid, casual work and not necessarily lead to greater gender equality.

2) At this years’ International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) annual Governing Council meeting in Rome, the Microsoft founder Bill Gates stated, “One of the most important priorities is connecting the poorest farmers in the world to breakthroughs in agricultural science and technology. Right now, a digital revolution is changing the way farming is done, but poor small farmers aren’t benefiting from it.”

From these two arguments, I discuss below what I believe agricultural value chain is, its relation to gender, the importance of capacity building, and the role of ICTs in strengthening the capacity of the actors to ensure food security.

Agricultural Value Chains

So what is all about the agricultural value chain? Before the 2008 hike in world food prices that created a global crisis and caused economic instability and social unrest across the globe, the agricultural sector was given very little attention by the donor community compared to other sectors like services and industry. With the revelation by the World Bank’s World Development Report (WDR) 2008 that GDP growth originating in agriculture is about four times more effective in raising incomes of extremely poor people than GDP growth originating outside the sector, a new stream of interest emerged to avoid such a global disaster again.

An Agriculture Value Chain Framework (Image Credit: GBI)

The value chain approach to agricultural development is one of the models, which basically places an emphasis on recognizing the relation between the various actors within the agricultural innovation system for smooth flow of resources and value adding process as products move from source of production to consumption. It aims at streamlining production and marketing activities to ensure that resource flow is coordinated and roles are well organized from the farm to the consumer. It identifies a set of actors and their respective activities that are aimed at bringing basic agricultural product from research and development, through production in the field, marketing and value adding processing to the final consumer.

Value Chain and Gender in Agriculture

So how can this model perpetuate gender stereotype? The traditional agricultural innovation system generally operates in isolation in terms of actors allowing them to exchange resources and transact businesses without any definite coordination of activities. As explained by the above policy brief, the modern value chain model may be key to food security, but can also be channels to transfer costs and risks to the weakest nodes, particularly women with the rapidly globalizing agricultural markets where the value chains are often controlled by multinational or national firms and supermarkets. In the modern value chain system, the paper pointed out, men are more concentrated in higher status, more remunerative contract farming, while women predominate as wage laborers in agro-industries. Also women workers are generally segregated in certain nodes of the chain (e.g. processing and packaging) that require relatively unskilled labor, reflecting cultural stereotypes on gender roles and abilities. FAO gender and food security statistics figures show 44.70% in 1950, 45.87% in 1970, 47.34% in 1990, 48.10% in 2000 (estimated) and 48.74% in 2010 (estimated) share of female labor force in total agriculture labor force.

Capacity Building and Value Chain in Agriculture

The gendered nature of agriculture – research, extension, and farming (as depicted by the figures in the previous section) does not only show how important it is to consider women in making decisions concerning the global agricultural development but also tells how their involvement will continue to rise despite all the stereotype. For both men and women to benefit from the modern value chain, the public and private sector approaches to agricultural research, development and extension has to be reconsidered. Capacity building for all the stakeholders must be directed at three components:

i) Institutionally, efforts must be made with the current value chain approach to seek gender-oriented, demand-driven research and extension activities. Institutions that give opportunity to stakeholders to contribute, share ideas and engage in constructive discussions will lead to sound innovations. Women put together have voice. Value chain projects must focus on farmer cooperatives with gender specific groups. Involvement of women must not be limited to only farming but extended to research and extension with more females motivated to take up key roles in these institutions.

ii) Humanly, while I believe there is so much efforts to improve the human capacity level of research and extension in some of these economies, my observation is that over 90% of this effort is targeted at the symptoms of the problem instead of the actual root cause. In other words, how much effort is being made to re-evaluate and re-structure the current educational institutions that produce the researchers and extension officers in these economies? That is the root of the problem. In-service training activities are short term strategies. Therefore long term strategies to help overhaul the existing educational systems in some of these economies will help address the human challenge.

iii) To achieve both the human and institutional capacities, there should be regular external technical support with material and human resources through sharing of best practices in agricultural research, extension and farming from other developing economies or developed countries. Efforts must be made also to capitalize on the strengths of receiving economies to be able to give the right technical advice.

ICTs for Capacity Building in Agriculture Value Chains

The second argument above argues that even though there is a digital revolution in farming, smallholder farmers are not benefiting. I will agree with the fact that smallholder farmers in some developing countries have seen increased access to agricultural information for production and marketing in the past decade, but this cannot be likened to a “revolution.” This increased in information to and from farmers cannot be compared to the speed at which the technologies are being developed. So there must be a problem somewhere.

The emerging communication technologies, social media and Web 2.0 tools are of no doubt critical in increasing capacity for timely data gathering, knowledge production, and information exchange even among illiterate farmers in developing economies. But how can this be done to benefit the target clients? Whose responsibility it is to spearhead the digital revolution among the smallholder farmers?

I believe much of the responsibility is on the donor community, the technology developers and the project implementers. As pointed out by the Bill Gates, the approach being used today to fight against poverty and hunger by the donor community – International Fund for Agriculture Development (IFAD), the World Food Program (WFP), and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and others is outdated and inefficient.

In other that the new communication tools such as mobile phones – feature and smartphones, iPad and other tablets, social media platforms like Facebook, YouTube, podcasts, audio and video conferencing, etc. to have impact on researchers, extension officers and farmers, new strategies have to be developed. Whether the National Agricultural Extension Services (NAES), the private sector extension services, or national research institutions, once the necessary capacity is built and tools provided, delivering information, technical advice and agricultural skills and training to farmers will follow.