I participated in a very informative event this week in Washington DC where a researcher was sharing his experience on “Weather-Index based Crop Insurance for Smallholder Farmers in Ethiopia”. As I listened to the discussion as an agricultural information specialist, my concern was what is the role of mobile technologies in this?

According to the researcher, Dr. Shukri Ahmed a Senior Economist, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the concept of crop insurance has a long history from Asia with the leadership of India. However, due to the challenges associated with insurance in general and access to credit to smallholder farmers, the idea somehow waned. But according to Index Insurance Innovation Initiative (I4), there is overwhelming evidence that uninsured risk can drive people into poverty and destitution, especially those in low-wealth agricultural and pastoralist households. There is therefore a re-emergence of insurance for smallholder farmers across the globe.

The speaker gave a detailed background to the study in Ethiopia and the importance of partnership in the design and implementation of the study. The difference, however, with this new approach to crop insurance for smallholder farmers is the use of index (indices) to support the insurance service, and intervention against emergency situation. But at the same time the study is targeting farmers that are relatively better off and who are already engaged in the market but are not investing in insurance due to the anticipated risks. The outcome of the pilot study is expected to help protect the livelihoods of smallholder farmers, who are vulnerable to severe and catastrophic weather risks particularly drought, enhance their access to agricultural inputs, and enable the development of ex-ante market based risk management mechanism which can be scalable in Ethiopia.

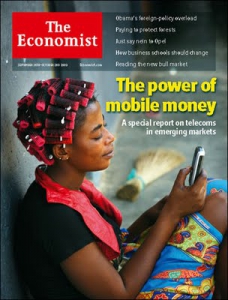

Unbanked or Branchless Services

Adding another concept to an already very complex issue that tries to combine weather, insurance, credit/finance, and smallholder farming, should be carefully considered. But the key question is whether mobile technologies can play a catalytic role in this entire complex system?

Among the reasons for choosing a given area for the pilot study, include availability of Nyala Bank branches, the vulnerability of yields to drought, the availability of nearby weather stations, and the willingness of cooperatives in the area to purchase the new product. As the pilot study progresses, the possibility of scaling the project across the country is high. But what will be the implications for the absence of banks in the rural farming communities in a country that has an approximately one bank loan per 1000 adults? Can Mobile Banking help understand why smallholder farmers under-investment in agriculture?

A success story of mobile banking by the Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited (DBBL) in Bangladesh was recently highlighted by the GSMA Mobile Money for the Unbanked. Interestingly, the story pointed out how DBBL learnt from Kenya’s famous mobile money program M-PESA. Kilimo Salama (KS) is an innovative index-based insurance product that insures farmers’ inputs (seeds, fertilizer, pesticides), and outputs (crop harvests), in the event of drought or excessive rainfall. It uses weather stations to collect data and implements SMS-based mobile technologies to administer and distribute the payouts. Mobile technologies will not only help with the financial transactions such as seen in Kilimo Salama’s case but also in support of the weather stations for timely and accurate decision making for pay-outs.

My conversation with Dr Shukri about the possibility of integrating mobile money into the project to address the challenge of absence of banks in rural Ethiopia, revealed the huge untapped market for Mobile Banking in that country. However, the success of such services depends on a convincing business case for both the banks and Mobile Network Operators (MNOs). Most importantly, however, is the state of telecommunication infrastructure and regulation in the country. These need to be in place for services and applications to thrive. With this huge investment

Outside Ethiopia, I believe it is time for African countries to take advantage of the increasing mobile phone penetrations in the continent beyond social networking to general development applications such as for agriculture, health, education, and rural development.

To listen to the audio recording of the event, visit Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).