Does ‘openness’ enhance development?

This was the question explored in a packed Room 3 (and via livestream and Twitter) on the last day of the ICTD2012 Conference in Atlanta, GA.

Panelists included Matthew Smith from the International Development Research Center (IDRC), Soren Gigler from the World Bank, Varun Arora from the Open Curriculum Project and Ineke Buskens from Gender Research in Africa into ICTs for Empowerment (GRACE). The panel was organized by Tony Roberts and Caitlin Bentley, both pursuing PhD’s at ICT4D at Royal Holloway, University of London. I was involved as moderator.

As background for the session, Caitlin set up a wiki where we all contributed thoughts and ideas on the general topic.

“Open development” (sometimes referred to as “Open ICT4D“) is defined as:

“an emerging area of knowledge and practice that has converged around the idea that the opening up of information (e.g. open data), processes (e.g. crowdsourcing) and intellectual property (e.g. open source) has the potential to enhance development.”

Tony started off the session explaining that we’d come together as people interested in exploring the theoretical concepts and the realities of open development and probing some of the tensions therein. The wiki does a good job of outlining the different areas and tension points, and giving some background, additional links and resources.

[If you’re too short on time or attention to read this post, see the Storify version here.]

Matthew opened the panel giving an overview of ‘open development,’ including 3 key areas: open government, open access and open means of production. He noted that ICTs can be enablers of these and that within the concept of ‘openness’ we also can find a tendency towards sharing and collaborating. Matthew’s aspiration for open development is to see more experimentation and institutional incentives towards openness. Openness is not an end unto itself, but an element leading to better development outcomes.

Soren spoke second, noting that development is broken, there is a role for innovation in fixing it, and ‘open’ can contribute to that. Open is about people, not ICTs, he emphasized. It’s about inclusion, results and development outcomes. To help ensure that what is open is also inclusive, civil society can play an ‘infomediary‘ role between open data and citizens. Collaboration is important in open development, including co-creation and partnership with a variety of stakeholders. Soren gave examples of open development efforts including Open Aid Partnership; Open Data Initiative; and Kenya Open Government Portal.

Varun followed, with a focus on open educational resources (OER), asking how ordinary people benefit from “open”. He noted that more OER does not necessarily lead to better educational outcomes. Open resources produced in, say, the US are not necessarily culturally appropriate for use in other places. Open does not mean unbiased. Open can also mean that locally produced educational resources do not flourish. Varun noted that creative commons licenses that restrict to “non-commercial” use can demotivate local entrepreneurship. He also commented that resources like those from Khan Academy assume that end users have a computer in their home and a broadband connection.

Ineke spoke next, noting that ‘open’ doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Sometimes power relations become more apparent when things become open. She gave the example of a project that offered free computer use in a community, yet men dominated the computers, computers were available during hours when women could not take advantage of them, and women were physically pushed away from using the computers. ‘This only has to happen once or twice before all the women in the community get the message,’ she noted. The intent behind ‘open’ is important, and it’s difficult to equalize the playing field in one small area when working within a broader context that is not open and equalized. She spoke of openness as performance, and emphasized the importance of thinking through the questions: openness for whom? openness for what?

[Each of the presenters holds a wealth of knowledge on this topic and I’d encourage you to explore their work in more detail!]

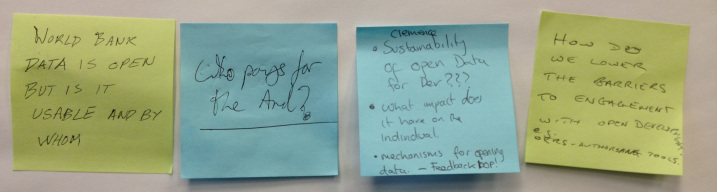

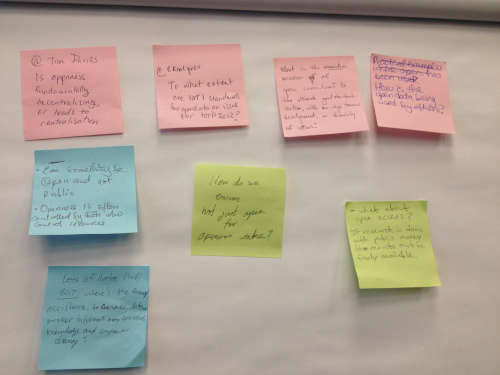

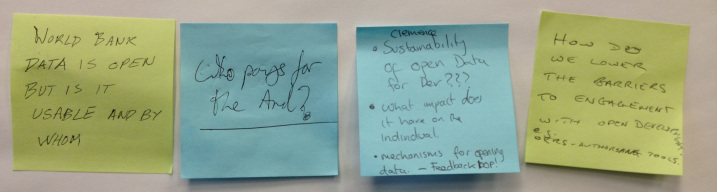

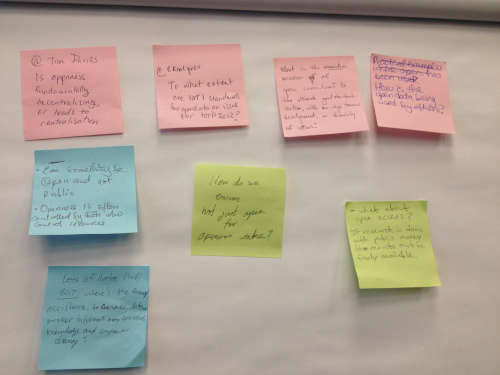

Following the short comments from panelists, the room split into several groups for about 15 minutes to discuss points, tensions, and questions on the concept of open development. (See the bottom of the wiki page for the full list of questions.)

Following the short comments from panelists, the room split into several groups for about 15 minutes to discuss points, tensions, and questions on the concept of open development. (See the bottom of the wiki page for the full list of questions.)

We came back together in plenary to discuss points from the room and those coming in from Twitter, including:

- Should any research done with public funds be publicly open and available? This was a fundamental values question for some.

- Can something be open and not public? Some said that no, if it’s open it needs to be public. Others countered that there is some information that should not be public because it can put people at risk or invade privacy. Others discussed that open goods are not necessarily public goods, rather they are “club” goods that are only open to certain members of society, in this case, those of a certain economic and education level. It was noted that public access does not equal universal availability, and we need to go beyond access in this discussion.

- Is openness fundamentally decentralizing or does it lead to centralization? Some commented that the World Bank, for example, by making itself “open” it can dominate the development debate and silence voices that are not within that domain. Others felt that power inequalities exist whether there is open data or not. Another point of view was that the use of a particular technique can change people without it being the express intent. For example, some academic journals may have been opening up their articles from the beginning. This is probably not because they want to be ‘nice’ but because they want to keep their powerful position, however the net effect can still be positive.

- How to ensure it’s not data for data’s sake? How do we broker it? How do we translate it into knowledge? How does it lead to change? ‘A farmer in Niger doesn’t care about the country’s GDP,’ commented one participant. It’s important to hold development principles true when looking at ‘openness’. Power relations, gender inequities, local ownership, all these aspects are still something to think about and look at in the context of ‘openness’.

The general consensus was that it is important to fight the good fight, yes, but don’t lose sight of the ultimate goal. Open for whom? Open for what?

As organizers of the session, we were all quite pleased at the turnout and the animated debate and high level of interest in the topic of ‘open development’. A huge thanks to the panelists and the participants. We are hoping to continue the discussions throughout the coming months and to secure a longer session (and a larger room) for the next ICTD conference!

Note: New Tactics is discussing “Strengthening Citizen Participation in Local Governance” this week. There are some great resources there that could help to ground the discussion on ‘open development’.

Visit the ‘does openness enhance development’ wiki for a ton of resources and background on ‘open development’!

The Africa Soil Information Service (AfSIS) makes one wonder how people coped before it existed. Africa Soil offers an enormous abundance of peer-to-peer information and services, namely data and maps that are georeferenced. The site fills a much needed gap because knowledge about the condition of African soils because it tends to be fragmented and outdated. AfSIS aims at giving the tools needed to maintain the health of the soil resource base as science and technological developments in remote sensing are providing new opportunities for low cost and efficient applications such as digital soil mapping, infrared spectroscopy, remote sensing, statistics, and integrated soil fertility management. Through such efforts areas of risk can be predicted and monitored.The Globally Integrated Africa Soil Information Service (AfSIS) is a “large-scale, research-based project to develop a practical, timely, and cost-effective soil health surveillance service to map soil conditions, set a baseline for monitoring changes, and provide options for improved soil and land management in Africa.”

The Africa Soil Information Service (AfSIS) makes one wonder how people coped before it existed. Africa Soil offers an enormous abundance of peer-to-peer information and services, namely data and maps that are georeferenced. The site fills a much needed gap because knowledge about the condition of African soils because it tends to be fragmented and outdated. AfSIS aims at giving the tools needed to maintain the health of the soil resource base as science and technological developments in remote sensing are providing new opportunities for low cost and efficient applications such as digital soil mapping, infrared spectroscopy, remote sensing, statistics, and integrated soil fertility management. Through such efforts areas of risk can be predicted and monitored.The Globally Integrated Africa Soil Information Service (AfSIS) is a “large-scale, research-based project to develop a practical, timely, and cost-effective soil health surveillance service to map soil conditions, set a baseline for monitoring changes, and provide options for improved soil and land management in Africa.”