- transparency and accountability as core values

- better coordination and program planning (internally and externally)

- reduced reporting burden (if donors agree to use IATI as a common tool)

- improved aid effectiveness

- collective learning in the aid sector

- improved legitimacy for aid agencies

- an opportunity to educate the donor public on how aid/development really works

- ‘moral ground’ for IATI compliant aid organizations to pressure governments and private sector to be more transparent

- space for communities and ‘beneficiaries’ to hold aid agencies more accountable for their work

- space for engaging communities and the public in identifying what information about aid is useful to them

- concrete ways for communities to contest, validate and discuss aid information, intentions, budgets, actions, results.

- Is IATI the right way to achieve the goal of transparency and accountability?

- Is the cost in time, money, systems, and potential risk of exposure worth the individual and collective gain?

- Is IATI the flavor of the month, to be replaced in 2-4 years?

- What is the burden for staff? Will it increase overhead? Will it take funds and efforts away from programs on the ground?

- What is the position of the US Government/USAID? Will implementing agencies have to report in yet another format (financial, narrative)?

- Much internal project documentation at NGOs/INGOs has not been written with the idea of it being published. There may be confidential information or poorly written internal documents. How will aid agencies manage this?

- What if other agencies ‘steal’ ideas, approaches or donors?

- What security/risks might be caused for sexual or political minority groups or vulnerable groups if activities are openly published?

- Isn’t IATI too focused on ‘upward’ accountability to donors and tax payers? How will it improve accountability to local program participants and ’beneficiaries’? How can we improve and mandate feedback loops for participants in the same way we are doing for donors?

- Does IATI offer ‘supplied data’ rather than offer a response to data demands from different sectors?

- technology’s impact on donor-sponsored technical assistance delivery, and

- private enterprise driven economic development, facilitated by technology.

Our meetings are lively conversations, not boring presentations – PowerPoint is banned and attendance is capped at 15 people – and frank participation with ideas, opinions, and predictions is actively encouraged through our key attributes. The Technology Salon is sponsored by Inveneo and a consortium of sponsors as a way to increase the discussion and dissemination of information and communication technology’s role in expanding solutions to long-standing international development challenges.

Does ‘openness’ enhance development?

This was the question explored in a packed Room 3 (and via livestream and Twitter) on the last day of the ICTD2012 Conference in Atlanta, GA.

Panelists included Matthew Smith from the International Development Research Center (IDRC), Soren Gigler from the World Bank, Varun Arora from the Open Curriculum Project and Ineke Buskens from Gender Research in Africa into ICTs for Empowerment (GRACE). The panel was organized by Tony Roberts and Caitlin Bentley, both pursuing PhD’s at ICT4D at Royal Holloway, University of London. I was involved as moderator.

As background for the session, Caitlin set up a wiki where we all contributed thoughts and ideas on the general topic.

“Open development” (sometimes referred to as “Open ICT4D“) is defined as:

“an emerging area of knowledge and practice that has converged around the idea that the opening up of information (e.g. open data), processes (e.g. crowdsourcing) and intellectual property (e.g. open source) has the potential to enhance development.”

Tony started off the session explaining that we’d come together as people interested in exploring the theoretical concepts and the realities of open development and probing some of the tensions therein. The wiki does a good job of outlining the different areas and tension points, and giving some background, additional links and resources.

[If you’re too short on time or attention to read this post, see the Storify version here.]

Matthew opened the panel giving an overview of ‘open development,’ including 3 key areas: open government, open access and open means of production. He noted that ICTs can be enablers of these and that within the concept of ‘openness’ we also can find a tendency towards sharing and collaborating. Matthew’s aspiration for open development is to see more experimentation and institutional incentives towards openness. Openness is not an end unto itself, but an element leading to better development outcomes.

Soren spoke second, noting that development is broken, there is a role for innovation in fixing it, and ‘open’ can contribute to that. Open is about people, not ICTs, he emphasized. It’s about inclusion, results and development outcomes. To help ensure that what is open is also inclusive, civil society can play an ‘infomediary‘ role between open data and citizens. Collaboration is important in open development, including co-creation and partnership with a variety of stakeholders. Soren gave examples of open development efforts including Open Aid Partnership; Open Data Initiative; and Kenya Open Government Portal.

Varun followed, with a focus on open educational resources (OER), asking how ordinary people benefit from “open”. He noted that more OER does not necessarily lead to better educational outcomes. Open resources produced in, say, the US are not necessarily culturally appropriate for use in other places. Open does not mean unbiased. Open can also mean that locally produced educational resources do not flourish. Varun noted that creative commons licenses that restrict to “non-commercial” use can demotivate local entrepreneurship. He also commented that resources like those from Khan Academy assume that end users have a computer in their home and a broadband connection.

Ineke spoke next, noting that ‘open’ doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Sometimes power relations become more apparent when things become open. She gave the example of a project that offered free computer use in a community, yet men dominated the computers, computers were available during hours when women could not take advantage of them, and women were physically pushed away from using the computers. ‘This only has to happen once or twice before all the women in the community get the message,’ she noted. The intent behind ‘open’ is important, and it’s difficult to equalize the playing field in one small area when working within a broader context that is not open and equalized. She spoke of openness as performance, and emphasized the importance of thinking through the questions: openness for whom? openness for what?

[Each of the presenters holds a wealth of knowledge on this topic and I’d encourage you to explore their work in more detail!]

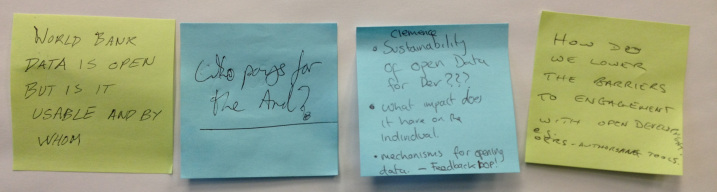

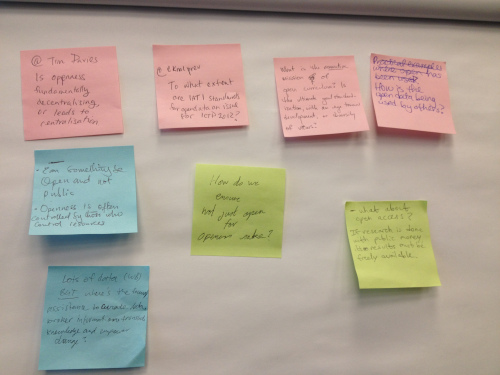

Following the short comments from panelists, the room split into several groups for about 15 minutes to discuss points, tensions, and questions on the concept of open development. (See the bottom of the wiki page for the full list of questions.)

Following the short comments from panelists, the room split into several groups for about 15 minutes to discuss points, tensions, and questions on the concept of open development. (See the bottom of the wiki page for the full list of questions.)

We came back together in plenary to discuss points from the room and those coming in from Twitter, including:

- Should any research done with public funds be publicly open and available? This was a fundamental values question for some.

- Can something be open and not public? Some said that no, if it’s open it needs to be public. Others countered that there is some information that should not be public because it can put people at risk or invade privacy. Others discussed that open goods are not necessarily public goods, rather they are “club” goods that are only open to certain members of society, in this case, those of a certain economic and education level. It was noted that public access does not equal universal availability, and we need to go beyond access in this discussion.

- Is openness fundamentally decentralizing or does it lead to centralization? Some commented that the World Bank, for example, by making itself “open” it can dominate the development debate and silence voices that are not within that domain. Others felt that power inequalities exist whether there is open data or not. Another point of view was that the use of a particular technique can change people without it being the express intent. For example, some academic journals may have been opening up their articles from the beginning. This is probably not because they want to be ‘nice’ but because they want to keep their powerful position, however the net effect can still be positive.

- How to ensure it’s not data for data’s sake? How do we broker it? How do we translate it into knowledge? How does it lead to change? ‘A farmer in Niger doesn’t care about the country’s GDP,’ commented one participant. It’s important to hold development principles true when looking at ‘openness’. Power relations, gender inequities, local ownership, all these aspects are still something to think about and look at in the context of ‘openness’.

The general consensus was that it is important to fight the good fight, yes, but don’t lose sight of the ultimate goal. Open for whom? Open for what?

As organizers of the session, we were all quite pleased at the turnout and the animated debate and high level of interest in the topic of ‘open development’. A huge thanks to the panelists and the participants. We are hoping to continue the discussions throughout the coming months and to secure a longer session (and a larger room) for the next ICTD conference!

Note: New Tactics is discussing “Strengthening Citizen Participation in Local Governance” this week. There are some great resources there that could help to ground the discussion on ‘open development’.

Visit the ‘does openness enhance development’ wiki for a ton of resources and background on ‘open development’!

Kayode Fayemi, Governor Nigeria’s Ekiti state, has declared yesterday his administration is ready to integrate fully Information and Communications Technology (ICT).

Kayode Fayemi, Governor Nigeria's Ekiti state, is happy about future the preliminary success of the Ekiti state's website. (image: file)

He even launched a new official website for the state. The new website will enhance accountability and transparency in governance he believes. The website is also expected to be interactive, easing access to government by providing diverse information on government activities.

The website also linked to Social Media sites like Facebook, Slideshare, Google Plus, Twitter, Flickr and YouTube, as well as mobile applications for Android and Blackberry devices, while Nokia and iPhone versions will be released within a month. Since its’ launch, the website has become the second most visited in Nigeria.

Ekiti is said to be the first state to have Quick Reference (QR) Codes integrated into its website. Fayemi also disclosed that his administration was providing laptops for students in public secondary schools.

While, the Ekiti State University (EKSU) is expected to be fully connected to the internet in two months time to allow students access to e-library. The site is expected to serve as an interactive platform between the people of the State and the government to get feedback and as means of engaging the younger generation.

Segun Adekoye

This is a guest post from Jamie Lundine, who has been collaborating with Plan Kenya to support digital mapping and governance programming in Kwale and Mathare. The original was published on Jamie’s blog, titled Information with an Impact. See part 1 of this series here: Digital Mapping and Governance: the Stories behind the Maps.

Mapping a school near Ukunda, Kwale County

Mapping a school near Ukunda, Kwale County

Creating information is easy. Through mobile phones, GPS devices, computers (and countless other gadgets) we are all leaving our digital footprints on the world (and the World Wide Web). Through the open data movement, we can begin to access more and more information on the health and wellbeing of the societies in which we live. We can create a myriad of information and display it using open source software such as Ushahidi, OpenStreetMap, WordPress, and countless other online platforms. But what is the value of this digital information? And what impact can it have on the world?

Youth Empowerment Through Arts and Media (YETAM) is project of Plan International which aims to create information that encourages positive transformation in communities. The project recognizes young people as important change agents who, despite their energy and ability to learn, are often marginalized and denied opportunities. Within the YETAM project, Plan Kenya works with young people in Kwale County (on the Coast of Kenya) to inspire constructive action through arts and media – two important channels for engaging and motivating young people.

Information in Kwale County

Kwale County is considered by Plan International to be a “hardship” area. Despite the presence of 5-star resorts, a private airport and high-end tourist destinations on Diani beach, the local communities in Kwale County lack access to basic services such as schools, health facilities and economic opportunities. Young people in the area are taking initiative and investigating the uneven distribution of resources and the inequities apparent within the public and private systems in Kwale County.

As one component of their work in Kwale, Plan Kenya is working with the three youth-led organizations to create space for young people to participate in their communities in a meaningful, productive way. There are different types of participation in local governance – often times government or other agencies invites youth to participate (“invited space”) as “youth representatives” but they are simply acting to fill a required place and are not considered within the wider governance and community structures.

Youth representation can also be misleading as the Kwale Youth and Governance Coalition (KYGC) reports that “youth representatives” aren’t necessarily youth themselves – government legislation simply stipulates that there must be someone representing the youth – but there is no regulation that states that this person must be a youth themselves (they must only act on behalf of the youth). This leaves the system open to abuse (the same holds true for “women’s representative” – you can find a man acting on behalf of women in the position of women’s representative). Plan Kenya and the young people we met are instead working to “create space” (as opposed to “a place”) for young people in community activism in Kwale County.

The 5 weeks we spent in Kwale were,the beginning of a process to support this on-going work in the broad area of “accountability” – this encompasses child rights, social accountability and eco-tourism. The process that began during the 5 weeks was the integration of digital mapping and social media to amplify voices of young people working on pressing concerns in the region.

To create the relevant stakeholders and solicit valuable feedback during the process of the YETAM work on digital mapping and new media, our last 3 days in Kwale were spent reviewing the work with the teams. On Thursday November 10th, we invited advisors from Plan Kwale, Plan Kenya Country Office, the Ministry of Youth Affairs and officers from the Constituency Development Fund to participate in a half-day of presentations and feedback on the work the young people had undertaken.

By far the work that generated the most debate in the room was the governance tracking by the KYGC. The team presented the Nuru ya Kwale blog which showcased 28 of the 100 + projects the youth had mapped during the field work. They classified the 28 projects according to various indicators – and for example documented that 23 of the projects had been completed, 1 was “in bad progress”, 2 were “in good progress” and 1 “stalled.”

The CDF officers (the Chairman, Secretary and Treasurer of the Matuga CDF committee in Kwale County) were concerned with the findings and questioned the methodology and outcome of the work. They scrutinized some of the reports on the Nuru ya Kwale site and questioned for example, why Mkongani Secondary School was reported as a “bad” quality project. The officials wanted to know the methodology and indicators the team had used to reach their conclusions because according to the representatives of the CDF committee, the auditors gave the Mkongani Secondary School project a clean bill of health.

One important message for the youth based on feedback on their work was the need to clearly communicate the methodology used to undertake the documentation of projects (i.e. what are the indicators of a project in “bad” progress? how many people did you interview? Whose views did they represent?).

There is significant value in presenting balanced feedback that challenges the internal government (or NGO) audits – for example the data on Kenya Open Data documents that 100% of CDF money has been spent on the Jorori Water Project mentioned above, but a field visit, documented through photos and interviews with community members reveals that the project is stalled and left in disrepair. This is an important finding – the youth have now presented this to the relevant CDF committee. The committee members were responsive to the feedback and, despite turning the youth away from their offices the previous month, invited them to the CDF to get the relevant files to supplement some of the unknown or missing information (i.e. information that people on the ground at the project did not have access to, such as for example, who was the contractor on a specific project, and what was the project period).

Kwale youth with staff from Plan Kenya, officers from the CDFC and the local Youth Officer

Kwale youth with staff from Plan Kenya, officers from the CDFC and the local Youth Officer

Samuel Musyoki, Strategic Director of Plan Kenya who joined the presentations and reflections on November 10th and 11th, reported that:

“The good thing about this engagement is that it opened doors for the youth to get additional data which they needed to fill gaps in their entries. Interestingly, they had experienced challenges getting such data from the CDF. I sought to know form the CDFC and the County Youth Officer if they saw value in the data the youth were collecting and how they could use it.

—

The County Youth Officer was the most excited and has invited the youth to submit a business proposal to map Youth Groups in the entire county. The mapping would include capturing groups that have received the Youth Enterprise Fund; their location; how much they have received; enterprises they are engaged in; how much they have repaid; groups that have not paid back; etc. He said it will be an important tool to ensure accountability through naming and shaming defaulters.

The 5 weeks were of great value — talking to quite a number of the youth I could tell — they really appreciate the skill sets they have received-GIS mapping; blogging; video making and using the data to engage in evidence based advocacy. As I leave this morning they are developing action plans to move the work forward. I sought assurance from them that this will not end after the workshop. They had very clear vision and drive where they want to go and how they will work towards ensuring sustained engagement beyond the workshop.”

The impact of digital mapping and new media on social accountability is still an open question. Whether the social accountability work would have provoked similar feedback from duty bearers if presented in an offline platform (for example in a power point presentation) instead of as a dynamic-online platform is unknown.

The Matuga CDF officers were rather alarmed that the data were already online and exposed their work in an unfavourable light (in fairness, there were some well-executed projects as well). There is a definite need to question the use of new technology in governance work, and develop innovative methods for teasing out impact of open, online information channels in decision-making processes and how this is or isn’t amplifying existing accountability work. There is definite potential in the work the young people are undertaking and the government officers consulted, from the Ministry of Youth Affairs and local CDF Committee (CDFC) stated that they were “impressed by the work of the youth”.

Within the community development systems and particularly the structure of devolved funding, there is a gap in terms of monitoring and evaluation (M&E) that the CDF committee to date has not been able to play effectively. As Samuel Musyoki stated the youth “could watch to ensure that public resources are well utilized to benefit the communities.” The Youth Officer even invited the youth to submit proposals for assistance in buying GPS gadgets and computers to strengthen this work.

Continuing the on and offline integration

As discussed, the work in Kwale on various issues is dynamic and evolving. The 5 weeks we spent with the teams were meant to provide initial trainings and support and to catalyse action that would be continued by the youth in the area, with support from Plan Kenya. Not only did we provide training to the young people, but Plan Kwale staff were also involved in the process and started documenting their work through the tools and techniques introduced by our team. With these skills, the Plan Kwale staff will support the on-going field mapping and new media work. We are also available to provide remote assistance with questions about strategies and technical challenges.

Some of the future activities include:

- Holding a “leaders forum” during which the youth interact with a wider cross-section of stakeholders and share their work.

- Continuing work on their various websites – updating the sites with results from social auditing work to be carried out throughout the last weeks of November, as well as digitizing previous information collected during historical social auditing.

- Validating the data by revisiting some project sites and documenting projects that haven’t been done yet, gathering stories from some of the Project Management Committees, taking more photos, and potentially conducting surveys within the communities to get more representative views on project evaluations.

- Each group also needs to develop a more structured advocacy strategy to direct their activities in these areas.

- All teams expressed interest in developing proposals to submit to the Ministry of Youth Affairs, through the Youth Enterprise Fund and CDF Committee, based on the suggestion of potential funding for this process. Plan Kwale staff, as well as some of the Country Office advisers offered to support the youth in developing these proposals.

- Most importantly, the teams want to consult the wider community in their respective areas to demonstrate the relevance of YETAM, including the skills they have gained, to the community stakeholders (beyond the relevant government authorities

The potential of new technologies, including digital mapping to promote accountability, is only as powerful as the offline systems into which it is integrated. Without offline engagement, existing community systems of trust and recognition will be threatened and thus undermine any online work. The youth must remain grounded within their existing work and use new technology to amplify their voices, build their network, share their stories and lessons and learn from and engage with others.

This is a guest post from Jamie Lundine, who has been collaborating with Plan Kenya to support digital mapping and governance programming in Kwale and Mathare.

Throughout October and November 2011, Plan Kwale worked through Map Kibera Trust with Jamie Lundine and Primoz Kovacic, and 4 young people from Kibera and Mathare, to conduct digital mapping exercises to support ongoing youth-led development processes in Kwale county. One of the important lessons learned through the Trust’s work in Kibera and Mathare is that the stories behind the mapping work are important for understanding the processes that contribute to a situation as represented on a map. To tell these stories and to complement the data collection and mapping work done by the youth in Kwale, the Map Kibera Trust team worked with the Kwale youth to set up platforms to share this information nationally and internationally. Sharing the important work being done in Kwale will hopefully bring greater visibility to the issues which may in the longer term lead to greater impact.

Sharing stories of local governance

To support their work on social accountability, the Kwale Youth and Governance Consortium (KYGC) mapped over 100 publicly and privately funded community-based projects. The projects were supported by the Constituency Development Fund (CDF), Local Area Development Fund (LATF), NGOs and private donors. As one channel of sharing this information, the Consortium set up a blog called Nuru ya Kwale (Light of Kwale). According to KYGC the blog “features and addresses issues concerning promotion of demystified participatory community involvement in the governance processes towards sustainable development. We therefore expect interactivity on issues accruing around social accountability.” This involves sharing evidence about various projects and stories from the community.

One example is the documentation of the Jorori Water project in Kwale; through the mapping work, the Governance team collected details of the constituency development fund (CDF) project. The funding allocated to upgrade the water supply for the community was 6,182,960 ksh (approximately 73,000.00 USD). From their research the KYGC identified that the Kenya Open Data site reported that the full funding amount has been spent.

A field visit to the site however revealed that project was incomplete and the community is still without a stable water supply, despite the fact that the funding has been “spent.”

Read more about the questions the team raised in terms of the governance of CDF projects, including the detailed the project implementation process and some reflections on why the project stalled. This is information on community experiences (tacit information) that is well-known in a localized context but has not been documented and shared widely. New media tools, a blog in this case, provide free (if you have access to a computer and the internet) platforms for sharing this information with national and international audiences.

Addressing violence against children and child protection

Another blog was set up by the Kwale Young Journalists. The Young Journalists, registered in 2009, have been working with Plan Kwale on various projects, including Violence against Children campaigns. The group has been working to set up a community radio station in Kwale to report on children’s issues. Thus far, their application for a community radio frequency has encountered several challenges. New media provides an interim solution and will allow the team to share their stories and network with partners on a national and internal stage.

The Kwale Young Journalists worked with Jeff Mohammed, a young award-winning filmmaker from Mathare Valley. The YETAM project not only equips young people with skills, but through peer-learning establishes connections between young people working on community issues throughout Kenya. The programme also provides young people with life skills through experiential learning – Jeff reflects on his experience in Kwale and says:

“My knowledge didn’t come from books and lecturers it came from interest, determination and persistence to know about filmmaking and this is what I was seeing in these Kwale youths. They numbered 12 and they were me. They are all in their twenties and all looking very energetic, they had the same spirit as mine and it was like looking at a mirror. I had to do the best I could to make sure that they grasp whatever I taught.”

Jeff worked with the Young Journalists on a short film called “the Enemy Within.” The film, shot with flip-cameras, tells the story of 12-year-old girl who is sold into indentured labour by her parents to earn money for her family. During the time she spends working, the young girl “falls prey of her employer (Mr.Mtie) who impregnates her when she is only 12 years old.” Jeff reflects that “early pregnancies are a norm in the rural Kwale area and what the young filmmakers wanted to do is to raise awareness to the people that its morally unacceptable to impregnate a very young girl, in Enemy Within the case didn’t go as far because the village chairman was bribed into silence and didn’t report the matter to higher authorities.” This is a common scenario in Kwale, and the young journalists plan to use the film in public screenings and debates as part of their advocacy work in the coming months.

Jeff and the Kwale Young Journalists shot the film in four days – they travelled to Penzamwenye, Kikoneni and also to Shimba Hills national park to shoot 7 scenes for the movie. Read more about Jeff’s reflections on working with the Kwale Young Journalists on his blog.

Sharing ecotourism resources

The Dzilaz ecotourism team – a group that encourages eco-cultural tourism in Samburu region of Kwale county — also integrated social media into their work. During the last week (November 8th-12th) the group set up a blog to market the community resources, services and products. They also plan to document eco-culture sites and the impact that eco-tourism can have on the community. As of November 10th, 2011 the Dzilaz team had already directed potential clients to their website and thus secured a booking through the information they had posted.

The importance of telling the stories behind the maps

One important component to mapping work is to tell the stories behind the map. The three groups in Kwale are working to build platforms to amplify their grassroots level work in order to share stories and lessons learned. The information documented on the various platforms will develop over time and contribute to a greater understanding of the processes at a local level where youth as young leaders can intervene to begin to change the dynamics of community development.

Launched in June, ICT for Democracy in East Africa is a network of organizations seeking to leverage the potential of information and communication technologies (ICTs) to enhance good governance and strengthen democracy.

Launched in June, ICT for Democracy in East Africa is a network of organizations seeking to leverage the potential of information and communication technologies (ICTs) to enhance good governance and strengthen democracy.

This initiative is funded by the Swedish Program for ICT in Developing Regions (SPIDER) and aims to promote collaboration amongst democracy actors in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. Member organizations in the network are Kenya’s iHub, the Kenyan Human Rights Commission (KHRC), the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), Women of Uganda Network (WOUGNET), Transparency International Uganda (TIU), and Tanzania’s Commission for Human Rights and Good Governance (CHRAGG).

iHub, an open space for the tech community in Kenya, hosted a governance workshop in October. The event brought together stakeholders in academia, government, civil society and the tech community to identify governance challenges—such as an uninformed or misinformed citizenry about their basic rights and an entrenched culture of corruption. The take away from the session was that ICTs—particularly mobile phones—provide citizens with the platform by which they can engage in governance solutions in a discreet, personalized way, anytime, anywhere.

In the wake of 2012 Presidential elections, citizens need to be better educated, informed and engaged in the political processes to avoid post-elections clashes as it was the case in 2007. To this end, KHRC plans to tap into the potential of ICTs to increase citizen participation, monitor human rights violations, monitor the electoral processes, monitor government fulfillment of promises, carry out campaigns and also inform and educate its constituents and the public on various human rights and governance issues.

Civic participation and democracy monitoring is relatively weak in Uganda given that only 59% of registered voters cast their ballots in the February 2011 presidential elections, according to SPIDER. The proliferation of ICT tools, their potential to enhance communication and improve access to important information creates an opportunity for improved citizen engagement and advocacy towards increased transparency and accountability.

Through the strategic use of ICTs, Women of Uganda Network (WOUGNET), aims to improve access to public services, increase efficiency, transparency and accountability of government and political processes to ensure that citizens are informed about government functions and promote efficient service delivery.

WOUGNET will particularly target women, in community based organizations (CBOs) located in the rural districts of Northern Uganda. WOUGNET aims build the ICT capacity of these (CBOs) to monitor public service delivery as part of its anti-corruption strategy.

Similarly, Tanzania’s CHRAGG is implementing a project that will create a system that will enable citizens to file complaints, check the status of already filed complaints and receive feedback through SMS. The project will help poor Tanzanians forego the transportation lodging costs involved in filing complaints in far off regional offices.

There are more than 1.2 billion young people aged between 15 and 24 years in the world, accounting for about 18 per cent of the world population, but living thousands of miles apart, rarely engaging with one another.

Multimedia platforms, like video, help the young, bright leaders of tomorrow engage in intercultural conversations—speaking beyond language barriers to provide a subjective youthful view of their countries and reducing cultural tensions for future generations.

The United Nations Alliance and the International Organization for Migration has united to celebrate the International Youth Day’s theme—Our Year, Our Voice—with their PLURAL+ Video Festival.

The video festival is an empowering tool for young people aged 9-25 to speak out about their opinions and experiences with migration and diversity.

“My video is about how I see diversity,” said 10-year-old Aarohi Mahesh Mehendale, winner of the PLURAL + 2010 International Jury Award (Age 9-12).

It would be amazing if we could live in peace and harmony and accept differences. I chose to do the video because I felt strongly about the topic

Through five-minute films, the applicants use their own views and voices to explore subjects about migrant integration, inclusiveness, identity, diversity, human rights and social unity, in an effort to foster globalized social harmony.

Developing countries are home to 87 per cent of youth who face challenges of limited access to resources, healthcare, education, training, employment and economic opportunities.

The PLURAL+ Video Festival is a form of video advocacy, a means for youth from developed countries to explore the challenges experienced by those in developing countries, and empathize with their struggles.

Although this project has good intent, the logistics of the equipment and details on how to film are largely inaccessible and problematic.

The PLURAL+ project intends to engage youth in video advocacy to foster understanding, but is missing a vital element—providing the actual video cameras and training on how to use them.

Although there are “useful links” on the website, this project should really consider partnering with an organization like WITNESS, who specialized in video projects in developing regions.

Having an alliance with an organization in this area of expertise can help prevent problems that PLURAL+ may encounter—making the project more useful for those youth in developing countries whose perceptions should truly be seen and heard.

Amartya Sen famously once observed that famines rarely occur in democratic or even relatively free societies, rather from inequalities built into the societal mechanisms of food distribution. The current famine declared by the U.N. in Southern Somalia, exemplifies his case and point.

New mobile technologies and ICTs in aid projects, however, can be used to streamline the coordination between aid organizations on the ground, populations desperate for aid delivery, and those funding the projects abroad—and make them more sustainable.

As Charles Kenny points out, the modern expansion of international markets and improved international assistance have drastically reduced the probability of famines solely resulting from weak governance.

Alternatively, the government—or those in charge—must deliberately choose to deprive their people of food and, “…actively exercise the power to take food from producers who need it or deny food assistance to victims,” Kenny writes in Foreign Policy.

The political atmosphere within the two regions of Southern Somalia is a huge factor towards the most recent accumulation of mass malnutrition and starvation.

Lacking a sovereign state, citizens must rely on the governance provided by the decentralized al Shabab—who blames food aid for creating dependency—which does little to ensure access to food, preventing malnutrition, or improving livelihoods of the population.

In February 2010, the militant group ousted the World Food Program (WFP), followed by their expulsion of three other aid agencies, where they were accused of spreading Christian propaganda.

Al Shabab removed the food aid earlier this month, declaring that agencies without hidden agendas were free to operate in their areas. Later, they announced that expelled agencies, namely WFP, remained banned.

Despite these efforts of dissuasion, WFP airlifted 10 tons of food to Southern Somalia last Wednesday. Mobile technologies can used to track this aid to ensure that it is kept out of the hands of al-Shabaab and into the hands of the malnourished.

Ensuring that they honor their word and delivering aid are two battles to overcome, encouraging harmony for further aid distribution is another.

If al-Shabab upholds their promise to allow food aid in the upcoming months, there should be coordination to make these programs and projects happen efficiently and sustainably—between Southern Somalia’s civil society, the government, and aid agencies who hold the resources.

Aid agencies should capitalize on ICTs to enhance the collaborative effort between organizations and individuals with eyes on the ground, and those pulling the funding strings up in Washington.

Edward Carr who works in famine response for USAID on the ground in the Horn of Africa, says,

…we are going to have to use our considerable science and technology capacity to really explore the potential of mobile communications as a source of rapidly-updated, geolocatable information about conditions on the ground to which people are responding with their livelihoods strategies

Although this new way of collecting information for benefit incidence analysis is useful for tracking who each dollar benefits, it is only resourceful in the long-term if put into a local social context.

Who is the most impacted, but most importantly, why- is what truly matters in the long run.

This summer I have wrote a lot about good governance programs to fight corruption, improve government effectiveness and accountability, and how they they are crucial to developing countries economic development, overall prosperity, and empowerment of civil society. One issue, however, can be the monitoring and evaluation of democracy and governance projects, which can sometimes be difficult–public opinion surveys as a form of measurement can be fraudulent, or uneven, and systems can be disorderly. Although ICTs are not a panacea for a development, they can help to streamline democratic and good governance strategies, and embolden civil society to play a participatory role. Some of the ways ICTs can be employed in democracy and governance projects, such as e-government strategies, election monitoring systems and enabling citizen media, can drastically improve the efficiency of these initiatives. Based on what I have learned so far, below are suggestions for monitoring and evaluation for an e-governance strategy, how to implement an election monitoring system from the beginning til the end, and how best to measure the effectiveness of citizen media:

1. E-government and Participation

- Benefits: Transparency can be enhanced through the free sharing of government data based on open standards. Citizens are empowered to question the actions of regulators and bring up issues. The ability of e-government to handle speed and complexity can also underpin regulatory reform. E-government can add agility to public service delivery to help governments respond to an expanded set of demands even as revenues fall short.

First, on the project level, question if the inputs used for implementation and direct deliverables were actually produced. The government’s progression or regression should not rely solely on this because there are other outside variables. For the overall implementation, ask if the resources requested in place, and were the benchmarks that were set reached? Featured below is a timeline on how to implement a good e-government strategy.

2. Strengthen Rule of Law with Crowdsource Election monitoring:

- Benefits: Support for election monitoring may be provided prior to and/or during national or local elections and can encourage citizens to share reports from their community about voting crimes, ballot stuffing and map these crimes using Ushahidi. By documenting election crimes, it can provide evidence of corrupt practices by election officials, and empower citizens to become more engaged.

- Drawbacks: Publicizing information to the broad public means without checking the information’s validity these systems can be abused in favor of one political party or the other, and elections can be highly contested.

Below are systematic instructions on how to implement the “all other stuff” needed for a election monitoring system, like Ushahidi:

Step 1. Create a timeline that includes goals you have accomplished by different marker points leading up to the election, and reaching target audiences

Step 2. The more information reports the better for the platform, but consider a primary goal and focus on filtering information about that goal to the platform, put it in the About section.

Step 3. Target your audience and know how they can be reached for example

- Community partners

- Crowd

- Volunteers

Step 4. Figure out who your allies are—NGOs and civil society organizations that will want to support, and provide resources for more free and fair elections in your country. Figure out what groups would be best for voter education, voter registration drives, civic engagement or anti-corruption. Building a new strategy on top of the already existing ones will help to promote the campaign and making it more sustainable overtime.

Step 5. Reach out and meet with the groups you have targeted—and make sure to identify people from that country living abroad, reach out to the diaspora. Ask yourself the following questions when the program is implemented: should all reports be part of the same platform? Should reports come in before voting begins or just offenses taking place during elections? What about outreach after the election takes place for follow-up M&E?

Step 6. Get the word out to as many citizens as possible using flyers, local media, and target online influencers, such as those on Twitter or Facebook. Attract volunteers to assist in the overall outreach and publicity plan—a volunteer coordinator, technical advisor and, if possible, a verification team or local representatives, to relay and confirm what monitoring the electoral processes is all about.

Step 7. Information sources:

- Mobiles: Frontline SMS can work as reception software for submissions via text.

- Email/Twitter/Facebook: Consider creating a web form to link people to on social networks which asks for everything you need, including, detailed location information, category and multimedia.

- Media Reports and Journalists: Have volunteers look in the news for relevant information to be included in the reports

- Verification team: Either a local organization or journalist works best—on site that is able to receive alerts from the platform on events happening around their polling stations to be able to verify what is going on. Cuidemos el Voto modeled Ushahidi slightly for incoming reports from whitelisted people to show up automatically, for example non-governmental election monitoring organizations.

Step 9. Monitoring and Evaluation

- Closing the loop of information: How will you show citizens who provided information on electoral fraud that you received it? Have a system in place to tell community representatives that the information was received and it will be acted upon.

- How will you act on that information in the country’s courtrooms, though? Make sure to preserve the documentation of election fraud that your platform has received so that it can serve to hold the perpetrators accountable in court.

3. Citizen Media

Citizen media allows content to be produced by private citizens outside of large media conglomerates and state run media outlets to tell their stories and provide bottom up information. Also known as citizen journalism, participatory media, and democratic media, citizen media is burgeoning with all of the technological tools and systems available that simplify the production and distribution of media

- Benefits: In addition to the above-mentioned benefits, citizen media also allows a sense of community where up-to date news covers a variety of angles, stories, and topics found in hard to reach places.

- Drawbacks: It can be risky for the citizens journalists and their supporters. They can be identified and targeted by members of the oppression, where they will be put in jail or tortured. There is no gatekeeping, verifying, or regulating the information—this is not a problem when it comes to video or photos, but definitely with information. Also, connectivity issues may not allow citizens to upload the information.

- Helpful Resources: This journalist’s toolkit is a training site for multimedia and online journalists.

- Monitoring and Evaluation for citizen media projects: Governments have foreign policy and economic agendas that guide their choices on how they fund projects, therefore, it’s important that the grantees and activists understand and share the same objectives. This is also beneficial to learn from projects over time to avoid redundancy and enhance efficiency of implementation.

- Measurement approaches—Some corporate funding agencies like the Gates Foundation, Skoll Foundation, and Omidyar Network insist on measuring citizen media projects, while other funding agencies like the Knight Foundation insist less on measurement. It’s important to measure both quantitative and qualitative outcomes and give constructive feedback to the contributors so that they can become more effective.

- Quantitative—Objectives may sometimes change in response to your context, but keep the end goal in mind, continue to measure yourself against the objectives. This can be done through web analytics or web metrics—website performance monitoring service to understand and optimize website usage

- Qualitative—Primarily anecdotal and used to shift policy objectives. In the end, however, it’s about visualizing the change you are trying to bring in the world, and making it happen.

The recent rebellions in the Middle East and North Africa have shown to the world the power of recording and disseminating revolutionary events often denied by oppressive regimes; and the proliferation of mobile phones has proved to be a necessary piece of media weaponry for these citizen journalists.

How then, can mobiles be used to maximize the efficiency of their citizen journalists?

The Mobile Media Toolkit created by MobileActive, clarifies problems that may arise while using mobiles in media and assists citizen journalists in their endeavors to deliver their own perspectives of events to the rest of the world.

The Toolkit—available in English, Spanish and Arabic—provides how-to guides, wireless tools, and case studies on how mobile phones are being used for reporting, news broadcasting, and citizen media.

Citizen journalists often report out of necessity so mobile phones are a rapid, covert, and cheap communications channel to suits their needs. In hostile regions where journalism is censored or banned altogether, citizen reporters must be prepared for reacting to quickly changing situations and security measures.

MobileActive’s online resource has information relevant for varying prototypes, from the basic Java phones to the latest smartphone. The tool kit has five main components consisting of:

- Creating the Content—Knowing how to capture multimedia enables reporters to capture breaking news and information at a moment’s notice. This section discusses capturing content (like photos, video, audio, and location information) on phones, both smartphones and otherwise; editing that content; (briefly) sharing that content online.

- Sharing Content from Mobile to Media—Explores content platforms that let mobile phone users (including trained journalists, untrained content producers, or even “readers”) easily upload content to various mediums. This section also looks at blogging, microblogging, and uploading multimedia.

- Delivering Content Online from Media to Media—Covers how to make content (text, audio, video, and more) accessible to a mobile audience in various ways, including text message alerts, audio channels like phone calls and radio, mobile web, mobile apps, and location-based services.

- Engaging the Audience—This section articulates how to engage audiences on their mobile phones to make it more participatory. Since social media has become an important conduit for engagement, understanding mobile social media, “listening” to the audiences are saying, and thinking about audiences as participants and content creators rather than passive recipients of content. The section focuses on helping media organizations see their mobile-using audiences as participants in the media process.

- Making Sure Information is Secure

- The Mobile Surveillance Primer helps identify and understand the risks involved with mobile communication in citizen journalist’s work. The Primer goes over basic mobile surveillance, and acknowledges what kind of information can be transmitted by or stored in your phone.

- The Tips and Tools section discusses specific use cases

- Mobile Active’s Security Risk Primer—to help activists, human rights defenders, and journalists assess the mobile communications risks that they are facing, and then use appropriate mitigation techniques to increase their ability to organize, report, and work more safely.

MobileActive’s new Mobile Media Toolkit covers all the bases in what citizen journalists should know about reporting with their mobile phones.

Hopefully this how-to initiative will encourage more citizen journalism efforts beyond the Middle East and North Africa to all repressive governments, enhancing efforts for citizens to hold their government’s more accountable and transparent.