It was a normal day by Accra standards. I walked out of the house ready to make my way to the center of town for an interview with a homegrown tech company; Esoko. I hailed a taxi and started haggling with the driver, once we had settled on a price, we were off on the traffic-ridden roads into central Accra. An average of 3-15 street vendors would emerge at the larger intersections and red traffic lights trying to sell us anything from fruits, jewelry, books, to shoes (don’t ask me how/who would try on shoes while driving!).

Thanks to our zealous vendors, the market played out right outside the taxi windows accompanied by the sounds coming from the taxi radio speakers: Ghanaian Hiplife music and commentary on everything and anything on life in Accra. In those moments, I was immersed in the familiarity and novelty of the experience, completely unaware how my perspective on the market, media and communications in Ghana was about to change in the next few hours.

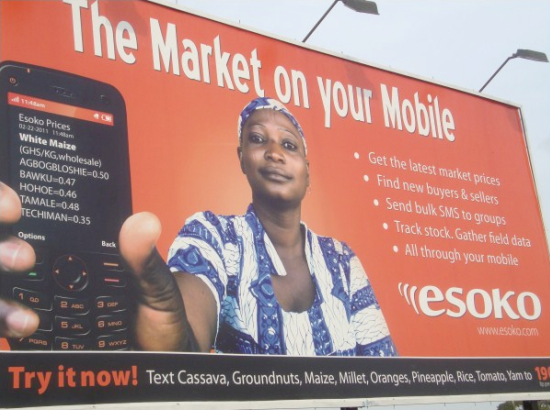

Below I detail what I learned from Sarah Bartlett (Communications Director) and Andrea Biardi (Technical Manager) who graciously sat with me and described the ins and outs of Esoko (Electronic Market, Soko = Market in Swahili), it’s role in Information and Communication Technology for Development and why it could be changing markets in Africa in unprecedented ways.

How did Esoko begin?

A decade ago Mark Davies, a Welsh-South African, fresh from the dot com boom made plans to travel across West Africa on his motorcycle. During this trip he interacted with both rural and urban communities and he kept thinking how life would be different for the people he was meeting if they had basic technology and infrastructure like stable power, printing services and internet; basically, services that people in the west took for granted. What kind of opportunities and innovation would arise from that consistent access to technology? Thus BusyInternet was born; initially an Internet Café, Internet Service Provider and a business incubator run in partnership with the World Bank.

BusyInternet provides basic technology services to the public and has grown into a successful technology hub located in Accra amongst the hustle and bustle of the Kwame Nkrumah circle. As it grew into the largest technology center in West Africa, Mark immersed himself in a new challenge. With mobile phones spreading rapidly and with so much data that needed to be collected and shared, especially in rural areas dominated by agriculture, it seemed the missing link was a technical platform that could facilitate.

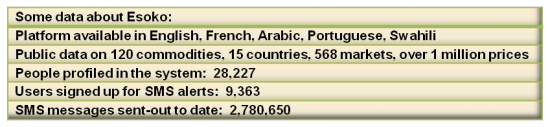

The idea of using mobile phones as that platform was obvious, as in Ghana the penetration rate for mobiles was upwards of 85% in city centers and averaging at 60% across the country. And it has continued to grow since: the International Telecommunication Union reported at the end of 2010 cellular penetration reached 75.4% across Ghana.

So in 2005, Mark and a few software developers started a new R&D company focused on local solutions to local problems using new technologies. Mobile phones played a key role. They created a plan to facilitate agricultural e-commerce under an endeavor they called ‘TradeNet’. Their first product became an application that enabled the dissemination and collection of price information for market commodities like grains and vegetables using simple SMS.

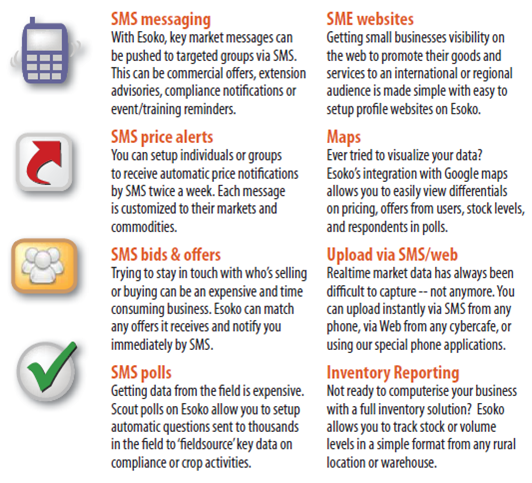

This information was accessible to anyone through the Internet but what made the tools from Esoko powerful and innovative was that you did not need a computer or the Internet to interact with the wealth of pricing information housed on the web server. With the simplest mobile phone, using basic SMS text you can access a world of pricing information. With the click of your mobile’s keypad or through auto-alerts customized for your needs the information would appear on your phone on a periodic feed. You therefore have access to the most up-to-date price information for the commodities of your choice be it coffee, cassava or wheat, at the tip of your fingers.

Mistowa and TradeNet: Before Esoko

In 2006 a partnership was formed between TradeNet and Mistowa, a regional program funded by USAID that aimed to remove trade obstacles in West African markets. Through this partnership, TradeNet emerged to provide an electronic agribusiness information exchange platform that enabled peer-to-peer trading. The initiative was able to offer access to real-time market information including commodity prices, offers to buy and sell between farmers, merchants and traders as well as business contacts on more than 300 products, from over 500 markets throughout West Africa.

TradeNet’s work with Mistowa brought to light the kinds of applications that would fulfill the needs of the agribusiness sector. And with 60% of Africans earn their living from working in agriculture, a sector so underserved in terms of technology solutions, it made sense for TradeNet to continue in that area. TradeNet started hiring more software developers, and the applications started getting more interesting.

By this time, there was a growing global trend in using mobiles/ICT to exchange information in a new way, shorten supply chains and get people better money for their crops. It had become resource-consuming to obtain information through the classical methods – collecting forms, using landlines, travelling to locations etc. Many projects and businesses were trying to create electronic systems to solve supply chain problems but were not technology experts or developers themselves.

Around this time, TradeNet re-branded itself as ‘Esoko’ or Electronic Markets (Soko is the Swahilli word for market) and became one of the pioneers in this growing field of African mobile innovation joining the likes of Ushahidi, Frontline SMS and SlimTrader, companies that are creating innovative mobile solutions specifically for the African customer. Esoko focuses on tools for market and agricultural information and is expanding its efforts into other realms whereas other companies in the sector focus on m-money, m-banking, crowd-sourcing disaster/phenomena data and so on. In a continent with such growing demand for mobile technology, it is exciting to see the variety and growing number of such technology companies creating solutions for the specific needs of the African customer.

Development Work, Local Interests and Sustainability

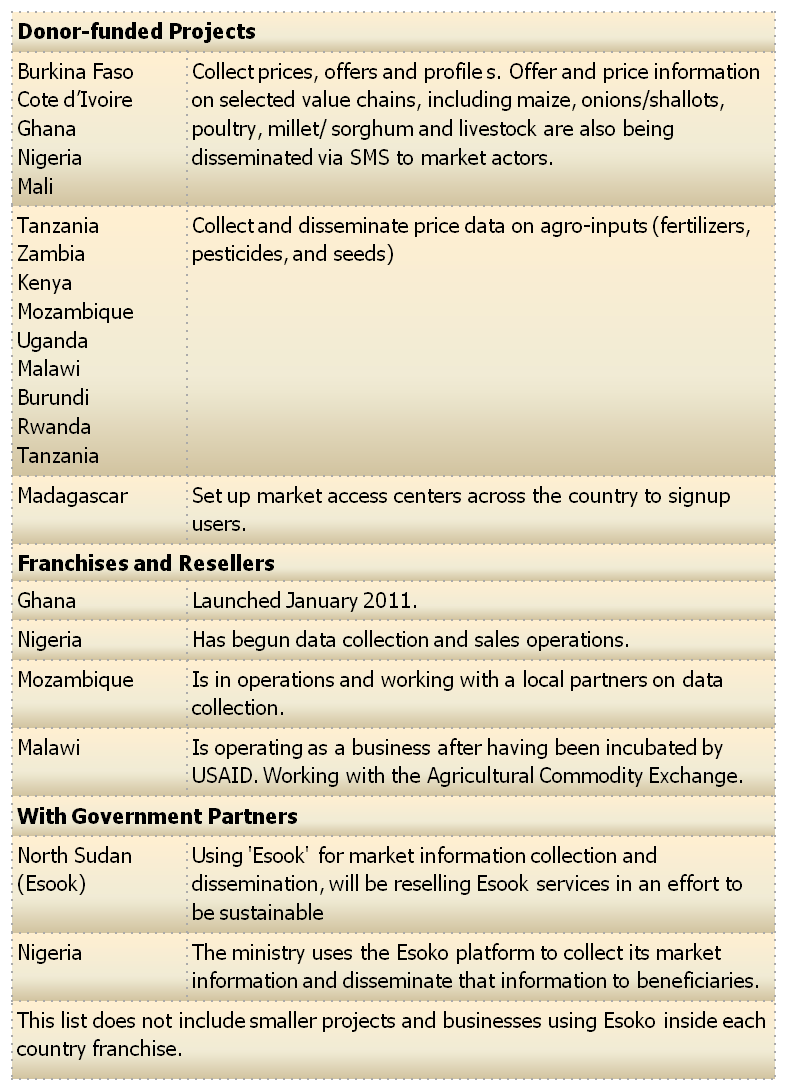

Many donor-funded development projects have similar challenges surrounding sustainability. Typically, when a project closes down, Esoko looks for a new partner in a new location. In many cases, these new partners have a different value chain or mandate and may be working with different end-users e.g. traders versus farmers.

In other scenarios somebody has to take over and continue to provide the services the community has grown accustomed to instead of a complete dismantling and scrapping of many months and years of work. In a new model, the project starts with government or donor funding and then transitions into a business; a franchise that can grow into a sustainable company. The first franchise launched in Ghana in January, 2011, will be a good model to pilot this potential solution toward sustainability.

Local businesses in Ghana are now using Esoko; utilizing some of their apps and services the same way that larger projects do. This kind of local interest also gives credence to the franchise model as there is demand in local markets for the products. Esoko has set up a shortcode across all the mobile operator services in Ghana on the phone line ‘1900’.; shortcodes in other countries have also been set up. Franchises in Nigeria and Mozambique have secured funding and are well on their way to launching. The USAID funded Market Linkage Initiative in Malawi is also working to develop a franchise as a part of its efforts.

In other countries, government entities like the Ministry of Agriculture in North Sudan and the Federal Ministry of Agriculture in Nigeria have tried to integrate the Esoko platform into their own methods. This will undoubtedly contribute to a sustainable presence of these services as they continue to evolve and integrate into how communities do business.

Sustainability through Best Practices and Failure

Over time, Esoko’s driving principle has evolved into actively seeking feedback from users and stakeholders to drive improvements and new product development. This ‘innovation driven’ approach allows the company and its products to stay relevant as it continues to bring real value to its customers. This ultimately leads to better sustainability and profitability.

This approach introduces a different accountability schema than is common in the development sector because as a business, Esoko is accountable to its bottom line – profit. This is very different from being accountable to the interests and discretion of donors who regulate the access and flow of steady funds. For this reason, Esoko would want to tell its stories of failure along with success so it can understand its own pitfalls and evolve more rapidly to meet customer demand.

User feedback from one partner to better the platform for their specific needs oftentimes ends up benefiting multiple partners. This is true for some of Esoko’s main offerings (the stock tracking application was initially designed and created for Esoko’s Sudanese partners) as well as small enhancements to the platform, like adding tagging and comment boxes to the price upload page. These comment boxes ended up transforming the tool into a sophisticated aspect of the price information product; introducing comments about quantitative price data took the product from a simple system to access price data to something that was stand-out from anything that was available in the market and can inform the user about markets in a multi-dimensional way. The product was simple enough to use, but also very powerful for its ability to provide qualitative price data such as explanations about price hikes and other price-related occurrences. Enhancements like this are continuous and Esoko’s partners are the driving force behind them.

Presence across the Continent: Esoko in Africa

The network is available across Africa with public data being available to all users. When Esoko representatives are out in communities doing training and in meetings, most users express their excitement about the technology; their reactions show the technology to be something they have long been waiting for and that feedback only adds to the excitement in Esoko’s main office. Once the technology is deployed, Esoko works closely to help local partners customize to the specific needs and cultural idiosyncrasies of that community.

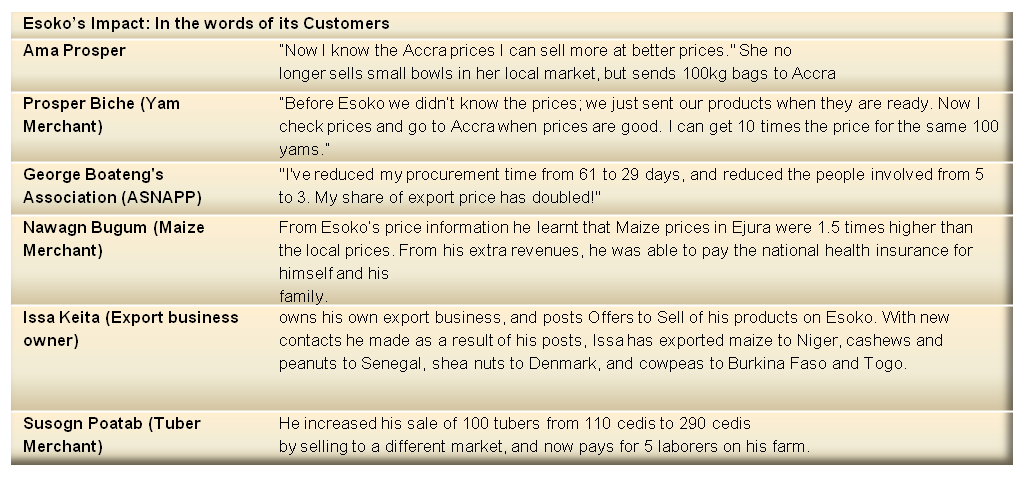

In November 2010 a survey of 62 farmers in Northern Ghana who have been receiving price alerts for one year confirmed that they have benefited from the service, with an average improvement of 40% on reported deals and revenue. 68% said they would be willing to pay around $1.30 a month, with another 29% suggesting they would consider it, and only 3% saying they would not. The users of the products have been able to make more informed decisions about negotiating better prices, selling farther away, selling as a collective and sending products to Accra on a mass scale. These findings and others about mobile usage have been building momentum for mobile tech and its role in development helping Esoko realize the importance and power of M&E data in telling the story of mobile tech in Africa to the world.

To go beyond anecdotal reports, Esoko has invited researchers to design third party evaluations for these SMS tools. The surveys would obtain quantitative data for M&E that could be very useful in showing how the tools are changing people’s lives as well as the supply chain. CIRAD, a French organization, did 600 surveys; 300 people who have been using Esoko tools for two years and 300 that have not but live in a similar community and similar conditions. Those results will be out at the end of 2011. In July of 2011 NYU’s CTED in Abu Dhabi began a study to evaluate the effectiveness of SMS-based market, taking three years to evaluate the impact of using Esoko tools on farm-gate prices and livelihoods (household assets and children in school), farmer marketing behavior (search behavior, bargaining power and market contracts) as well as the trust of other market players, especially traders. They will also gather data to find out how information spillovers and technology adoption occur among rural farmers in Africa.

Mobile Tech is a field replete with opportunities for research. There are many questions that would help understand the technology landscape, its impact and inform approaches when designing new mobile technology interventions in African markets. What is the correlation between mobile technology and development? How does the introduction of mobile technology affect communities and market systems? These questions are of interest to the larger global community as well as to local communities. Two research evaluations already done in India and Niger show that the introduction of mobile technology (voice-only) increased revenues to actors along the supply chain. These findings are cited countless times and have driven innovation as well as policies. New research about data-focused technology can lead to findings and similar implications.

Made in Africa by Africans

Esoko’s employees are mainly Ghanaian and West African, with 3 African diaspora employees and 4 US/European expats. Visiting employees typically come for 6 months to bring in knowledge about the latest technology. Currently there is a group of 60 young professionals at Esoko by building and supporting the technology. The truly exciting thing about the work Esoko is doing is that it is coming from Africa, and that it is complex technology. Esoko today has a solid user interface, a strong API to communicate with all the different mobile providers to get data from the field processed and then sent out via SMS to end users, and a complete setup of staff and developers comparable to a tech company anywhere in the world.

Impact: Business for Profit & Social Value – Disrupting the Market

According to Esoko, it is a company for profit and for social good because the two come hand in hand. The company has the intention of enabling better transparency, heightening efficiency across value chains and spreading information as well as helping organizations, businesses and individuals get to their bottom lines faster.

As far as innovative technology, the products are designed not to totally reinvent the market, but to make markets more efficient through the presence of the right tools. These tools and solutions are enablers that let people access information more quickly, easily and cheaply by putting the power for decision back in the hands of the customer. This will likely affect the way people do things, however, it is difficult to say how exactly it will change the market.

For businesses, this means tools so they can do business better; source goods locally, tighten supply chains, and make real time decisions based on quickly sourced field information. For individual farmers who have begun using Esoko, the tools have started skewing the market in ways that are easy to recognize because there is a high level of isolation typically experienced by rural producers. If a farmer has pricing information for regions more than two markets away she might forgo selling her products through several middle-men traders that would buy from her and sell at a different market. With the information at hand she could make a cost-benefit analysis to decide if it is best for her to sell her commodities far away herself or to trade with the middle-men. This decision might eliminate her need to work with middle-men who could take her product and sell it for a larger margin of profit or exploit her for their benefit. Armed with the correct pricing information, she can also negotiate a better price with the middleman. This would likely disrupt the market in unprecedented ways because none of the tools are designed to manipulate the market in any specific way. The tools are simply enabling access to information that would put the power for decision back in the hands of the customer.

Cultural Considerations

Each country may have specific user interaction needs, which translate into Esoko helping both projects and businesses deploy properly in their markets. For example Ghana has market queens for each commodity where merchants work under the main queen. Enumerators, who collect price data from markets on a regular basis for the franchise, go into each large market and approach the queens. The queens then have to be ‘courted’ and shown how they can also benefit from allowing Esoko in the market; the goal being that the queen would give approval and Esoko can become operational in that market. The enumerators continue to visit the queen and the markets enabling Esoko to culturally integrate with the market.

In one instance that illuminates the cultural elements and the benefit of ‘design for the customer’ approach, Kumasi’s market queen was putting high taxes for importing onion from Burkina Faso leading to the creation of a renegade onion trade happening on the streets to forgo the market. While the queens have the power to slightly fix the price in Ghanaian markets, Esoko is able to use features like comments on pricing data to describe the dynamics that play into the fluctuation of prices. This qualitative data helps makes sense of the quantitative price data as well as the cultural and socio-economic context of events in the market.

Esoko is a new inventive breed of African technology company. As the demand for cellular technology continues to grow rapidly, the relevance and impact of mobile innovators will also grow for the African market. With a projection of 170% growth for mobile phone usage (85% growth in smart phone use and 150% in non-smart phones) across Africa in the coming 5 years, technology innovators have the opportunity to impact the market in unprecedented ways that increase transparency, simplify supply chains and maximize benefit to the users. It is becoming increasingly hard to imagine that this kind of technology would not have a significant impact on Africa’s development.