Last week’s Tech Salon, hosted by ICT Works and the UN Foundation Technology Partnership, asked “Can youth find economic empowerment via apps, m-payments and social media?” I did a bit of reality checking and wrote in my last post about some of the ways that youth in African countries are harnessing ICTs to generate income. And it’s not really through apps, Facebook and mPayments.

So if developing apps isn’t the key to unlocking youth’s economic potential, is there another way that ICTs can support youth economic empowerment? At the Tech Salon we discussed a few other options.

Microtasking

Samasource’s work with “microtasking’ looks pretty interesting. TxtEagle, another microtasking initiative, just raised 8.5 million in start-up funding.

Txteagle is a commercial corporation that enables people to earn small amounts of money on their mobile phones by completing simple tasks for our corporate clients.

The types of tasks Txteagle’s African workers have done are:

- enter details of local road signs for creating satellite navigation systems

- translate mobile-phone menu functions into the 62 African dialects (for Nokia)

- collect address data for business directories

- fill out surveys for international agencies

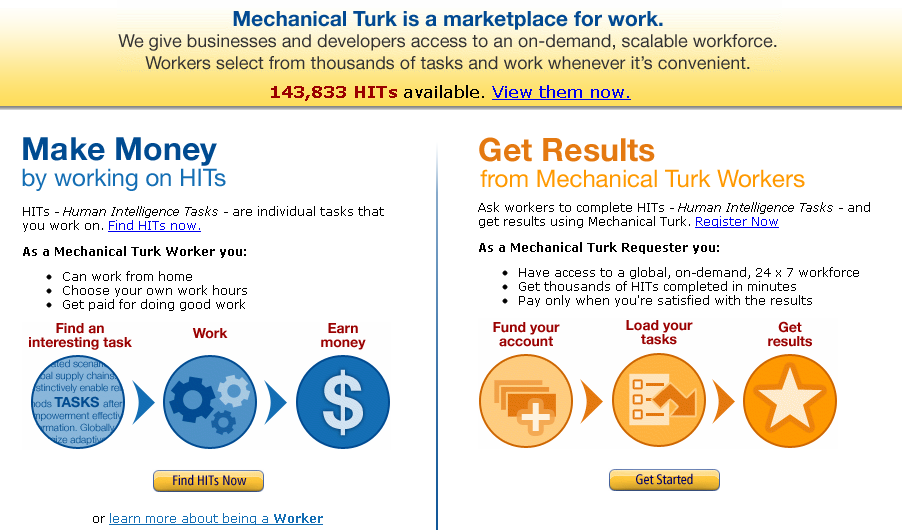

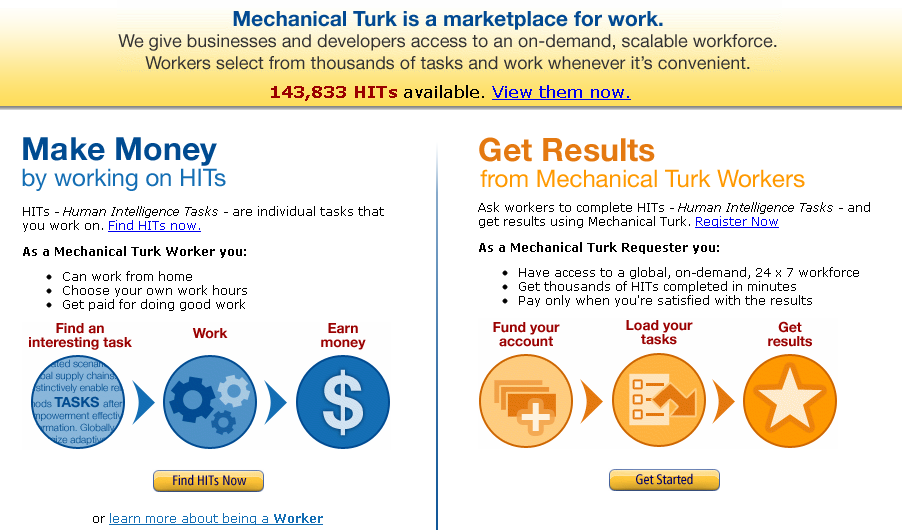

Txteagle seems similar to Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, except that workers only need a simple mobile phone – no computer or Internet access is needed.’

I hadn’t been paying attention to the microtasking phenomenon, so I did a little digging after the Tech Salon. Microsoft Research did an interesting study called Evaluating and Improving the Usability of Mechanical Turk for Low-Income Workers in India. They found some issues with the interface and make up of Mechanical Turk that made it difficult for low-income workers to benefit and provided some suggestions to improve micro tasking and make it accessible for low-income workers or those with lower education levels. When they improved the interface and instructions (in local language), test subjects’ ability to complete a task rose dramatically. “The most striking result of our study is that there exist tasks on MTurk for which the primary barrier to low-income workers is not the cognitive load of the work itself; rather, workers are unable to understand and navigate the tasks due to shortcomings in the user interface, the task instructions, and the language utilized.”

I’m sure we’ll be hearing lots more about microtasking (and I’m probably really late to the party here). It seems more reasonable that rural youth could access microtasking work than that they would develop their own apps.

De-skilling

Others at the Technology Salon talked about de-skilling and the job potential that can open up for youth when technology or better access to information allows them to take on roles formerly reserved for more skilled professionals. It seems this is going on quite a bit in the health sector, for example. The de-skilling phenomenon has been around for awhile but I hadn’t seen it as a way for youth in rural areas to access jobs and income, so I thought this was quite interesting.

I’m not sure how much de-skilling is being seriously looked at as a way to connect youth to jobs, or how many youth it’s employing in the rural areas, but it is something I’ll be keeping an eye on and learning more about. I’m thinking that many of us have been looking at de-skilling as a way to engage community volunteers in improving other aspects of community development, eg., allowing community health workers to do their volunteer work more efficiently; but not so much as an income generator for youth.

Job matching and mobile marketplaces

My Finnish colleagues sent me some other examples of mobile (SMS) initiatives that could support economic empowerment and that are good for pushing thinking on how rural youth could tap into opportunities. I think the key is that for now, anything aimed at rural populations needs to be SMS based, as mobile internet is still very uncommon in most rural areas. There’s no harm in planning for the day when most people have Internet-enabled phones, but for now, we’ll probably want to work with what people have, not what we wish they had….

- Google SMS Applications allow you to use some Google services via SMS text message.

- Esoko consists of mobile updates for farmers and traders delivered by SMS that include market prices and buy/sell offers, bulk SMS functionality, websites for small businesses and associations, and SMS polling technology. Their blog (which I spent some time on today) is great for sharing how they are going about getting Esoko to function well. Again it’s clear that the technology is the tip of the iceberg….

- Tradenet is a fully mobile integrated buy and sell portal in Sri Lanka. It has agricultural prices as well.

- Babajob is a job matching service from India that is fully mobile integrated.

- Cellbazaar is an SMS marketplace in Bangladesh.

- Tagattitude is a service that allows international mobile money transfers and purchases; eg., remittances.

- Souktel’s JobMatch uses SMS to connect employers with youth looking for jobs.

What else?

In addition to micro tasking and mobile applications, there are some more formal technology education programs such as the CISCO Networking Academies, not to mention plenty of locally created computer and technology academies and schools that formally train youth on ICTs with the aim of generating employment. I wonder though how many of the local training academies are focused on more traditional aspects of technology (eg., if you walk into one of these, do you see a room of oldish desktop computers?) and how many are also combining computer education with mobile, and advancing their education and training curricula as technology advances? Colleagues in Egypt told me that some initiatives exist that train up young people to repair cell phones. I’m wondering if this is widespread in other places as well. In any case, formal training opportunities are still difficult for youth in rural areas, and especially girls, to access.

In Kenya the government is promoting community digital centers through an initiative called the Pasha Centers. These centers are linked to youth structures in the constituency areas. Colleagues of mine reported that youth are accessing loans from the government youth fund and starting cyber kiosks, and mPesa centers that are promoting mobile banking.

On top of the government or NGO programs, the mobile phone industry itself opens a job market for young men and women who know how to set up phones, register SIM cards, etc., and there is a whole side industry, obviously, around mobile phones. But again, the more formal opportunities are in the capital or in secondary cities which can still be quite distant from where rural youth live.

Though use of apps, mPayments and Facebook may not be so widespread at the moment in the places I’ve traveled and where my colleagues are working, as outlined in post 1 of this series, and it’s not at all common for rural youth to develop applications themselves, there do seem to be some other possibilities for ‘youth economic empowerment’ that have a mobile or ICT component. I’m sure there are things I’ve missed out as well, that could be quite inspiring.

The question is how to connect these new opportunities with the young people who are typically excluded: youth in rural areas, especially girls. How to scale up the opportunities while ensuring that they are adapted to local contexts, which can vary significantly. Do youth in rural communities have the education levels and skills to access microtasking and to take advantage of ‘de-skilling’ opportunities on a broad scale? Do they know how and where to access microtasking jobs. How are the connections being made with these opportunities? Who has access to these kinds of jobs? How can rural youth find out about these opportunities?

In my next post, I’ll cover some of the other considerations for youth economic empowerment that we discussed at the Tech Salon.