Last week’s Tech Salon, hosted by ICT Works and the UN Foundation Technology Partnership, was on the topic ‘Can youth find economic empowerment via apps, m-payments and social media?’ Fiona Macaulay from Making Cents and I gave some of the opening remarks to get the conversation started (and Wayan Vota kept things lively as usual).

The premise of the Salon was that ‘today’s youth population is the largest in the history of the world, and 90% of these young people live in developing countries. The global youth unemployment rate is the highest on record, and we’re seeing discontent and disenfranchisement play out on the news each day. In fact, the revolution in Tunisia started with an under-employed youth committing self-immolation in frustration…. Technology-based models hold great promise for increasing and improving economic opportunities for young people: low barriers to entry for youth-built apps, the widespread use of Facebook and its promise as a marketing platform, the ubiquity and ease of m-Payment systems like MPESA – these should be a recipe for youth economic empowerment.

During the Salon we explored 3 key questions:

1) How are youth starting businesses or getting jobs in growth-oriented ICT sectors around the world?

2) How are organizations and programs utilizing technology to reach and engage young people?

3) Where should we be cautious or enthusiastic with technology with respect to youth economic empowerment?

This is the first of 3 posts on those questions, starting with Question 1:

How are youth starting businesses or getting jobs in growth-oriented ICT sectors around the world?

I was pretty skeptical about the potential for apps, Facebook and m-payments to resolve the youth employment/income crisis, at least in the context of the rural communities in Africa where I’ve worked over the past several years. So leading into the Salon, I did an informal survey among some colleagues working in Africa to find out how they observed youth making money using technology, and to see whether the idea above had any legs. My thoughts were pretty much confirmed – in the places we are working, some youth are using technology to generate income, but not so much apps, mPayments and Facebook.

In Egypt, colleagues said that youth are repairing cell phones, serving as DJs at wedding parties, setting up photocopy shops and internet cafes, selling phone calls and airtime, running shops that provide children and young people with the opportunity to play games, and using computers to make flyers and posters for certain producers and products in the communities. They also provide satellite connections for poor families to access national and international TV channels – this service is not legal but generates good income for young people.

In Kenya you’ll find youth managing Mobile Phone Kiosks popularly known as ‘Simu Ya jamii’ (community phones). These double up as phone charging points. Pirated music is big business for some youth and phone unlocking services are increasing. One colleague noted that youth are not really creating applications, but in some of our programs, they are involved in piloting new applications, and thus influencing their development. In Zambia, you don’t see much of this type of activity in rural areas, according to a colleague there. But there are village telcos being operated by youth groups and some village groups are setting up banks of solar chargers to support solar lighting. (Cool result: When they set them up at a schools, encouraging women to come each day to charge their lights, they found that school attendance increased).

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LTAbe35YCLY]

In Burkina Faso it’s common to see youth selling telephone scratch cards, renting out their phones, offering video services to film at private events, charging up phones for a price. In Senegal, some take phones from one area to another to charge them up for a fee. All over Africa you see video pirating and movie houses, video game houses, video downloading to mobile phones, music on flash drives and flash drives that plug into radios in cars and in collective transportation vans and busses.

There is ‘negative’ business also

Some would place ‘pirating’ and stolen satellite connections here. There is also transactional sex by girls to obtain mobile phones, which are a status symbol. We hear in some communities that adolescents with mobile phones are ‘bad.’ In Cameroon girls said that some boys only use phones to scam people and to steal. Mobiles can also facilitate prostitution. One colleague commented that in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) she has seen girls on motorbikes offering themselves by presenting their phone number on their back. We heard from youth in Cameroon that mobiles are commonly stolen and traded. Some parents in various countries do not like movie and game houses, associating them with porn and western culture.

Are youth in rural areas creating ‘apps,’ using ‘apps’ or tapping into ICT development or programming opportunities?

Not really, from what I have seen and what colleagues tell me. There are some shining stars here and there, but this isn’t very widespread yet, and the youth who are developing apps and such tend to be well-educated urban youth. This 2009 study on how the African Movement of Working Children and Youth (MAEJT) uses ICTs is quite interesting in this regard.

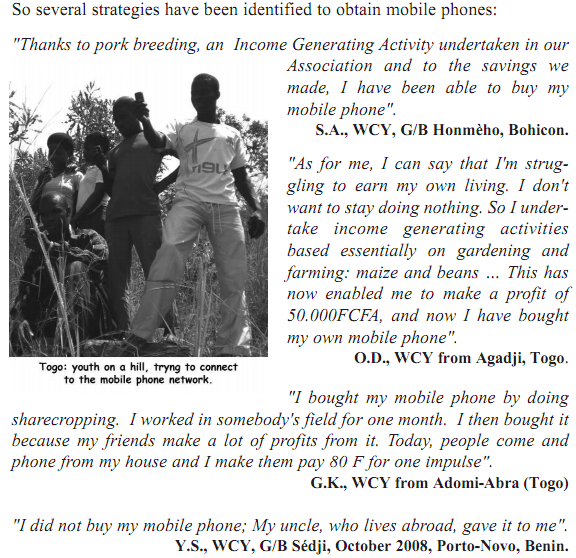

- How do youth obtain and use mobiles? (MAEJT study, 2009)

In Egypt, colleagues said Facebook and Twitter groups around specific issues are common among young people in communities. But using ICT specifically for generating income is not. There is inadequate awareness among poor communities on how to make this happen. Although many youth have access to cell phones, ICT is still expensive and non-affordable for many others. Most of the families who have phones in their houses do not have a direct line, which means that they cannot get access to internet through cheap lines. Internet is still very expensive. Getting jobs through the internet is only common among advantaged, well- educated youth, not disadvantaged youth.

In Nairobi, Kenya, iHub and NAiLab have a big pool of developers and there is a lot of action. In rural Kenya, however, access is limited. There is a lot of interest from the youth who have started to catch on though, so colleagues felt it was possible that there could be some type of rural-urban mentoring or connections to help rural youth get on board. In rural Zambia, according to colleagues, sheer poverty means that very few additional resources and capital are available to take on new ideas. There is still very poor mobile phone coverage in some areas, and many young people have already left for urban areas. My colleagues in West Africa did not report seeing any youth developing apps or using Facebook combined with mPayments to generate income. In Kenya, Cameroon, Uganda and some other places, innovation hubs and labs are generating opportunities, but these again seem to be available to secondary- or even more often university-educated youth from urban areas and capital cities or large cities outside the capital.

So, is this bit about apps, mPayments and social media all hype? I’ll explore that a bit more in post 2 of the series. In post 3, I’ll cover the longer term considerations for ICTs and youth economic empowerment and some broader aspects that need to be kept in mind.

Just last month, USAID Moldova sponsored the Moldova ICT Summit 2011, featuring the Association of Private ICT Companies in Moldova, as well as the recently launched national E- Government Center. The event focused on the e-transformation of the Moldovan economy, and the importance of e-transparency, among other topics.

Just last month, USAID Moldova sponsored the Moldova ICT Summit 2011, featuring the Association of Private ICT Companies in Moldova, as well as the recently launched national E- Government Center. The event focused on the e-transformation of the Moldovan economy, and the importance of e-transparency, among other topics.